Defining “jazz” has always been a difficult process. Though it is commonly held to be an (if not the) original American art form, detailing what makes music “jazz” has not been so simple. Differences of opinion abound regarding its sources and, perhaps even more, its seminal performers.

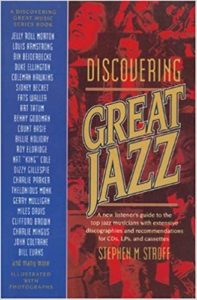

As the former jazz editor for the collector’s publication Goldmine, Stephen Stroff has heard many albums in his life that would apparently fit under this amorphous umbrella. With this experience behind him, Stroff has taken the opportunity to authenticate his opinion through the release of this new book, in which he takes fellow fans through his rendition of musical history, marking the crossroads with bold-print signposts and at times under-developed cross-referencing.

Though he claims that personal tastes “played but a small part,” the nature of any historical record is the promotion of the author’s opinions. Even so, though some of Stroff’s artist bios and definitions of jazz terminology (and further his choice of which terms and artists deserve attention) may be questionable (especially to the jazz-educated who may have their own ideas and favorites), it is hard to argue with the occasionally-syncopated chronological organization and the focus Stroff pays to “great legends” like Beiderbecke, Armstrong, Parker, Davis and Coltrane. Jazz is, after all, an exclusive club, and though this apparent fact may be somewhat to the detriment of jazz labels, it is often much to the delight of erudite aficionados.

From the revolutionary recordings of the Original Dixieland Jass (sic) Band to the frightening frontiers of the Marsalis family, Stroff points out the logical points of interest with educated anecdotes and a somewhat comprehensive research. Along the way, he presents some of the “best” recorded examples of the artists discussed (prompting major investment by those who wish to get the full measure of the book) and a random sampling of photographs and “basic jazz terms.”

Premising his book as “a refresher course for those who know what happened … and an education for those who don’t,” Stroff admits to the difficulties of recording and prognosticating on musical history. That said, a bit more attention to terminology and supporting players and bit less editorializing (e.g., claiming Davis’s “Bitches Brew” was “a rather sad plea for attention”) might have served Stroff better on his difficult and well-trodden road.